Want to know what an MVP is, the most common pitfalls, and what methods we can use to implement it? See how Elon Musk, Tesla’s CEO, used this innovation deployment model to achieve the desired effect, bypassing the trap of premature optimization and focusing on gradually scaling the brand’s offerings.

1. What is MVP in terms of creating digital products?

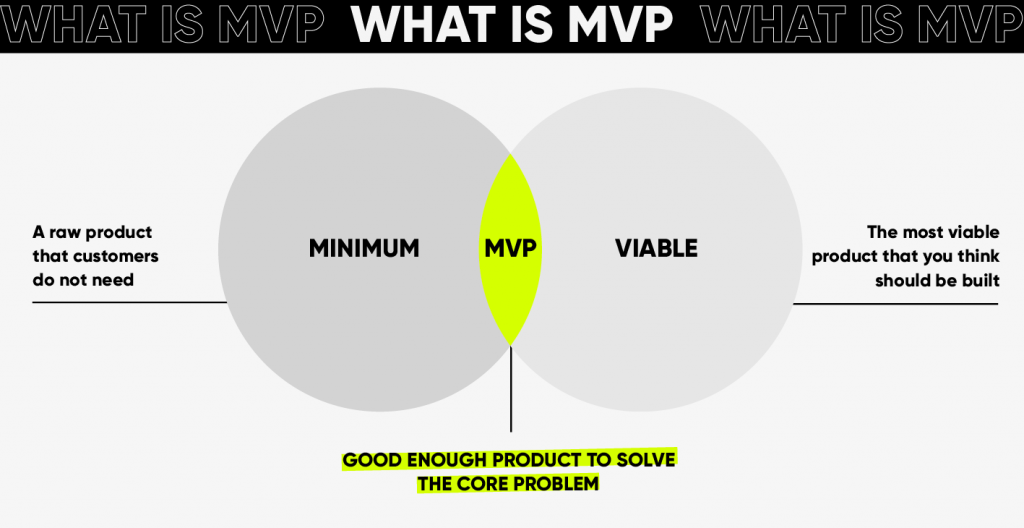

MVP – is an acronym for the phrase minimum viable product. In the context of creating digital solutions MVP is the version of a new product that allows the team to gather the maximum amount of proven customer knowledge with the least amount of effort. The main assumption for the separation of the scope and implementation of the MVP is to validate the idea and basic functionalities in terms of attractiveness for users, market demand for the product, and building the interest of future consumers/users.

The implementation of the MVP enables the product and value proposition to be checked under “combat conditions”. The user has a chance to provide feedback on the solution, and the software producer has a chance to establish a relationship with the user in the hope of turning an ambivalent user into a tester with a keen interest in product development (a user who will go crazy when the next version of the software is released).

An additional advantage of a properly defined and implemented MVP is lower costs if there is a need to implement changes. A change or a total pivot in the implemented solution, which is only a part of a larger tool, is less costly than the case of modifying the entire software (in the traditional philosophy of developing digital products, a finished product should be implemented on the market).

In the digital world, the concept of MVP has been promoted as part of the idea of Product Development (author: Steve Blank) and Lean Startup (author: Eric Ries). Both in their books on, among others, the development of digital products (“The Startup Owner’s Manual: The Step-by-Step Guide for Building a Great Company”, S. Blank, B. Dorf; “The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses ”E. Ries) present a concept where product implementation starts with an MVP. Subsequently, decisions on the implementation of further features should depend on the business strategy and feedback from users/consumers.

2. Proto-MVP – a trap in defining the minimum viable product scope

Before we move on to a specific example of MVP implementation, let us discuss one of the most common pitfalls that software developers fall into, and which the Tesla discussed below managed to avoid. Let us start by recalling an obvious regularity – the lion’s share of software success is user satisfaction. A satisfied user who can achieve his goals thanks to the tool and to whom the tool brings clear benefits is a potential promotional link. It is hard to find a more effective advertisement for your product than a delighted customer. Unfortunately, it works the same (or even more so) in the opposite direction. As consumers/users, we are much more willing to share our frustrations and negative feelings about a given brand with others. Such a pattern has its roots already in the early stages of the evolution of the human species – when something bad happened, we encountered a poisonous fruit, some danger was approaching, we warned as many people as possible, but when something good happened (e.g. we had a great partner) we reserved this information for the closest group. That is why “bad PR” has greater carrying power and that is why the first impression is so important in building brand loyalty.

Depending on the industry, the variables that make up a positive first impression may differ slightly. However, some variables can be considered a common denominator for almost all industries and are an important part of the first impression – including the real value that the user gains from the very beginning of using the product. Such a real value may be a specific solution to the problem that the user is struggling with, it may also be the fulfillment of his / her needs related to a specific aspiration. In both cases, knowledge of the problem/need is required to be able to correctly address the solution that will encourage users to use the tool.

Let us make a small digression here – one of the artifacts that is often obtained as a result of working on UX / CX is persona.

A persona is a simplified image of a group of future/current product recipients, often containing basic demographic information, a set of goals/motivations, a short biography, and the problems that users face during various activities. The purpose of carrying out this exercise and creating a persona is to empathize with the future user – understand who they are, what they do and how do they it, and what are their aspirations in the area of our interest.

A persona can be created in two ways:

1) by conducting a series of interviews with users, getting to know them personally;

2) creating an abstract image of the user based on our knowledge of who he is and what he needs, without consulting the user.

A persona created in a second way is called a proto-persona (from prototype). The proto-persona is better than the lack of a persona because of the very activity aimed at understanding the user, but the most effective method of getting to know the user and his problems is a direct conversation with the user.

The same is true for creating an MVP scope. The trap that innovators often fall into is implementing what can be called proto-MVP. That is the scope of the MVP, which is not consulted with the target user or is not based on a clear need communicated by consumers. Proto-MVP innovators are usually focused on the solution itself and comparing their vision to the competition, without consulting the direction in which they want to develop their software with future recipients. As a result, there are software similar to competing ones – without a clear point of difference, interesting unique proposition value, and MVP that does not build loyalty. They do not constitute an attractive innovation for users, which is worth devoting more attention to the further phases of product development. Luckily for the electric car industry, Tesla didn’t start with a proto-MVP, but with an MVP set in the context of real consumer demand.

3. Unique value proposition – the foundation of an effective MVP

A unique value proposition is one of the most important components of the success of a digital product. It can be described as the most important benefit that the user will have when choosing a product. Without consciously defined and addressed value in the product, the success of the tool is a lottery with a low probability of winning. Therefore, isolating the real need of users/consumers and addressing it as a UVP in the MVP is a necessary step in building customer loyalty.

When Tesla was founded in 2003, a consumer who was potentially interested in switching from a petrol engine car to an electric one had a headache that none of the current electric car brands was able to remedy. The portfolio of electric vehicles back then was filled with examples of cars, which, in the overall balance of advantages and disadvantages, discouraged potential consumers from deciding on a costly investment that then required considerable courage and faith in the development of infrastructure enabling the charging of electric vehicles. The typically electric cars available on the market drastically stood out from the combustion ones in terms of range (the 2009 BMW MINI E model could travel about 160 km on a single battery charge), additionally, electric cars were small, often 2-seater vehicles, unable to compete with combustion cars in speed range. There were many promises that Tesla had to fulfill in order not to be classified as another electric car which is an ecological compromise.

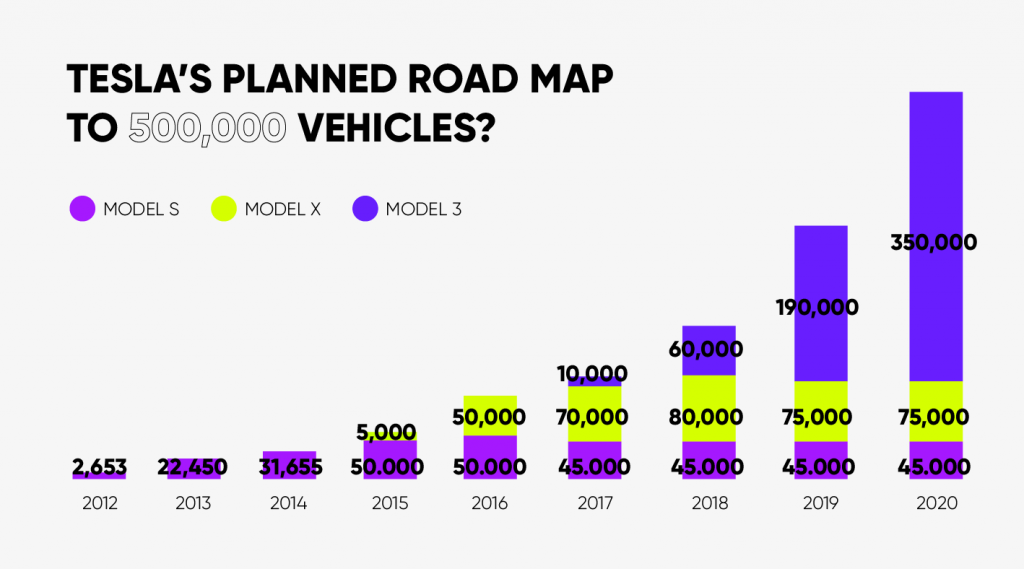

In 2006, Elon Musk, the then (and present) CEO of Tesla, announced in the pages of the blog “The Secret Tesla Motors Master Plan” – a strategy in which he shared with readers how he wants to achieve the target product (that is – to create inexpensive, 100% an electric car available to an average wealthy consumer). At that time, reaching this goal required some intermediate steps due to the enormous costs and time-consuming nature of creating a solution that would increase the competitiveness of electric cars (the feasibility of which was not yet seriously thought about by anyone). The first step was the implementation of the MVP – the first car that will communicate the brand’s UVP and will contain part of the promise of the target product. The profits from the MVP were allocated for investment purposes enabling the creation of another model that was closer to the target promise, another model financed the next one … and so in 2022 Tesla already offers several cars, with each subsequent model approaching the promise made in 2006.

When Tesla released its MVP – Tesla Roadster I in 2007, it was clear that it was possible to create a car whose UVP not only differs from the competition of electric cars but is not a compromise to combustion cars. Tesla Roadster I was able to cover about 400 km on one load (other electric cars from that period covered 100 – 160 km), had 250 Hp, and was able to accelerate to 100 km / h in 3.8 seconds – it was fast, it could cover more than 2x the distance than other competitors and was electric. Tesla’s MVP strategy did not end with the Tesla Roadster, however. It is not enough to have an electric car, you still need to be able to charge it somewhere, so after the release of the first car, the brand promised to significantly expand the network of charging stations for electric vehicles. Users could not only cover longer distances with the electric car but also had a choice of an increasing number of charging stations (currently Tesla has a network of over 30k “Superchargers” – fast charging stations). In this way, Tesla, by releasing the MVP of the target product, communicated its vision of the development of the electric automotive industry and the complementarity of the proposed solutions by expanding the infrastructure of charging stations for electric vehicles and (most importantly) handed over its mission of gradually phasing out combustion cars emitting carbon dioxide.

4. How did Tesla skip the premature optimization trap?

Very often, when we focus on satisfying a large number of people in some area of our life, we end up in a situation in which we fail to satisfy anyone (including us). We assume that, unfortunately, each of us has heard or experienced a comparable situation empirically. A similar pattern can be seen when implementing the MVP. When introducing their products, many innovators are overwhelmed by the mania to satisfy as many consumers/users as possible from the very beginning, focusing their efforts on developing a range of MVPs that will satisfy hundreds, and thousands of users immediately after implementation. They try to anticipate the bottlenecks of the implemented business model before implementing it. The trap of trying to match the scope of the MVP to a wide audience is called the “premature optimization trap” and often ends with the implementation of the MVP, which only contains teasers of various features, aimed at attracting a wide audience of users without focusing entirely on their problem. Innovators who fall into this trap, rather than focusing on one / two core functions through which the product UVP will speak, try to cram as much “incomplete” functionality into the software as possible to show the user a vision of the final solution. After all, they are just watered-down demos of unfinished functions that don’t solve any targeted user problem. Such an MVP model is often not remembered by consumers, so it does not build brand loyalty either.

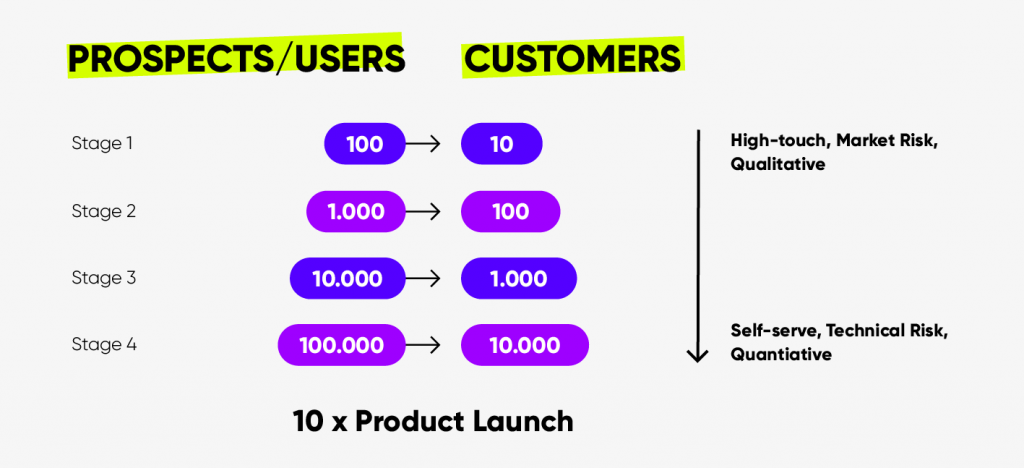

One of the paths worth considering to avoid the “premature optimization trap” is a product scaling strategy called “10x Product Launch”. It involves implementing MVP with the satisfaction of the first 10 users in mind. When we take care of the appropriate level of satisfaction of the first 10 customers and we recognize that our MVP is well received, customers are satisfied and willing to use the product – we automate or otherwise develop new functions focusing on the satisfaction of the number of users 10 times greater than the previous one, i.e. 100 … then 1000… 10,000, etc. The number 10 is a conventional number in this strategy and its purpose is to indicate the dynamics of scaling the product that we should adopt – if we are not able to satisfy a small number of users, in this case, 10, why should we succeed with 1000?

At the initial stage of product development, it is very important to have access to quality insight from users/consumers – so that we know not only what is going wrong or what users like, but also that we know the answer to the question of why this is so. Focusing on meeting the expectations of a smaller group of users significantly facilitates the smooth flow of information on the satisfaction with using the MVP and potential areas for improvement. It is worth remembering that the development of digital products is never linear, it is always more like an exponential curve, more figuratively speaking – it is shaped like a hockey stick. The growth of users/consumers does not have a constant value, and “accelerates” when the product reaches the next popularity level. The 10x Product Launch strategy is effective because it makes you think about scaling your product according to the dynamics of user growth in a non-linear, hockey stick-like manner.

In this way, Tesla also managed to avoid the “premature optimization trap”. Tesla began its expansion in the electric car market by creating a product that was to meet the needs of a narrow niche of customers. On this basis, the team wanted to evaluate the effectiveness of the most important elements of the car in practice, those elements that were responsible for keeping the brand promise (a battery that allows a longer ride on a single charge and an engine that allows an electric car to compete with sports cars equipped with a gasoline engine in terms of speed). Tesla Roadster I was a sports car that could be afforded by a decided minority of society, thus it was easier to get to know the target group, meet its expectations, and communicate with it in the area of potential changes leading to the improvement of subsequent models dedicated to a wider audience. To increase the effectiveness of communication and to ensure a coherent message shaping the image of the brand, Tesla did not (and still does not) have dealerships in the distribution network. From the very beginning, the brand focused on close contact with the customer, which resulted in the creation of a community of Tesla owners and facilitated honest feedback on potential improvements.

5. (not) all roads lead to the MVP

There are certainly several paths to implementing an attractive and business-effective MVP, but not every digital product development process leads to the identification of the scope of a successful MVP. The list of factors that must be met for the MVP to be remembered by users is long and not always easy to determine. We have already said about the core component of MVP – we cannot lose sight of users. The scope of the MVP must be a response to the real needs of users/consumers, focusing on providing a product thanks to which the user/consumer will achieve his goal – how you will achieve it is a secondary issue for the user. That is why, in the approach to the implementation of the MVP scope, it is so important to search for solutions creatively. History knows many examples of MVPs that provided the expected value and were the seeds of great success, although they were tool patchworks.

Let us focus on examining two alternative ways of delivering MVP. The first approach, called Concierge MVP, as in the case of a real Concierge service, is about delivering value to the target consumer by doing a given area of activity for him. In practical terms, this means that if in the MVP area we identify a key functionality that is important from the perspective of building user loyalty from the first implementation, but we are not able to deliver it in an automated form (because it requires a longer development time / more fund), we should consider a semi-manual method. For example, let’s assume that in preparing the MVP for a tool dedicated to booking visits in various private clinics, the following problem occurred – at the implementation stage, it was not possible to finally integrate the functionality of our tool that would allow the user to mark a visit as booked in the clinic system. The user has access to the schedule of unreserved appointments and can choose the preferred date, but after clicking ‘book an appointment, the date is not booked in the clinic’s system. According to the Concierge MVP model, we could make sure that the last, problematic step of booking a visit – marking the booking in the medical facility’s system – was done by making a phone call to the appropriate clinic and informing that patient X had booked an appointment on a specified date. This is not the most efficient booking method but would help deliver the expected value for the end user, by the way, we could evaluate the attractiveness of our tool concept while working on fully automating the process.

The second method is the so-called Wizard of Oz MVP. Here, if it is not possible to implement the entire key functionality in MVP, we focus on the implementation of its part, which is the essence of UVP, with our efforts, trying to “fill in” the rest of the scope using solutions already available on the market. A great example of an MVP implemented in this way is the Tesla Roadster I. When Elon Musk decided that the brand’s MVP would be an electric sports car, one of the dilemmas he faced was reconciling his visionary ambition with time and available resources. Designing such a car from scratch – both the external design and internal systems would require the involvement of resources that he did not have at the time. How did he keep his promise of an uncompromising electric sports car despite a lack of resources? Thanks to prioritization. Musk found that the most important element behind the brand’s UVP is an engine capable of competing in terms of speed with gasoline cars, equipped with a battery that can provide x2 longer driving on a single charge, compared to the then-available electric cars. He wanted to have the greatest control over the quality of these components, so he concentrated Tesla engineers’ efforts on the battery and engine, “complementing ” the rest of the MVP with an already available solution – he purchased a license for the existing Lotus Elise sports car. This is how the Tesla Roadster I was born with an engine and battery designed by Tesla engineers and the appearance of a Lotus Elise. Simple, brilliant, and effective.

6. Wrap-up

Until today, no recipe has been invented for “brewing” the ideal essence of MVP, applicable in various industries. Probably there is no such recipe. If the product is innovative and has new functionalities – it requires testing with users. The constant exposure of users to new solutions, in new software, changes the habits and standards of users – it means that the baggage of experiences and heuristics of users are also changing. That is why it is so important not to succumb to the so-called Innovator Bias.

Despite the lack of a perfect recipe for guaranteed MVP success, we have included in this article some practices that can bring any software developer closer to success. Designing digital solutions is not about bending users’ needs to a solution proposed by an innovator. Already at the MVP stage, the user must understand the value of using your tool (UVP) and whether he will be able to solve real problems thanks to it. Not every functionality (even though it seems to be crucial) can be provided to the user in the MVP. Therefore, it is worth remembering other tools that have already been tested. There may be a solution that saves resources while maintaining UVP quality. If not, it’s possible that some part of the software’s work can be done “semi-automatically” – so that the MVP remains attractive to users. After the implementation of the MVP, it is important to scale it gradually – if through MVP we can satisfy and build a loyalty-based relationship with several users, it means that we are ready to focus on addressing the needs of a wider group of users in the tool.

Let’s talk together about your MVP!

If you want to know more about MVP and digital click here and subscribe to our newsletter!